The future of academic library leadership

I’m a librarian. I’m also fortunate enough to have a library leadership position as an AUL at McMaster University. Where I work is not irrelevant for any discussion of the future of academic library leadership, as anyone who follows libraryland news well knows.

For a number of years it’s been clear to me that we’re not going to be able to master the tasks that arise from the evolution of libraries if we continue to insist on having too many influential positions in the library saddled with the “ALA-accredited MLS or equivalent” requirement. That’s not a revolutionary thought at this stage, but even jobs where that requirement has been softened to allow those with other educational pedigrees to apply tend to include required or clearly preferred qualifications that only a librarian would possess, making them de facto open only to librarians.

Parallel to the discussion of whether to open our positions to non-librarians is a neverending discussion around the lack of qualified applicants for library leadership positions. There seems to be general agreement that libraries do a poor job of creating qualified and eager successors.

Put these two factors together, and what emerges from all of this is that we (MLS-holding library administrators who are open to hiring non-librarians into key roles) could essentially be closing the door behind us for those in our own profession. The logical next evolutionary step would be that library leaders are no longer former line librarians, and that we are essentially the dinosaurs roaming the halls. There are, of course, library leaders already who did not come from the ranks, but doesn’t it follow that in 15-20 years, library directors with an MLS will be a very rare breed? Does that matter? I seem to think it does, but that leaves me with a bit of a paradox: how to get today’s work done and help create the next generation of library leaders. It’s not a simple task.

Experiential learning for the humanities

In a meeting at MPOW yesterday, the topic of experiential learning opportunities for humanities students came up. This topic speaks to me, not least because my educational background is in the humanities, but also because I spent a year in the late 90s doing a grant-funded research project that was essentially one large experiential learning opportunity. My boss asked us for ideas, and I wrote mine up in an email. I thought it made sense to publish them here as well since broader feedback would be helpful, and I’m sure there are aspects and opportunities to which I’m entirely blind. Please feel free to share any comments and suggestions.

Here’s what I wrote, edited to generalize the context: Read more…

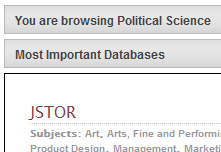

JSTOR and leading students astray

An August 22nd article in Inside Higher Ed confirms what anyone working with students in academic libraries at least suspects: students have incredibly poor information searching habits. I look forward to reading more about the research done in Illinois. One particularly distressing point from the summary worth highlighting is that JSTOR “was the second-most frequently alluded-to database [n.b.- behind only Google] in student interviews.”

An August 22nd article in Inside Higher Ed confirms what anyone working with students in academic libraries at least suspects: students have incredibly poor information searching habits. I look forward to reading more about the research done in Illinois. One particularly distressing point from the summary worth highlighting is that JSTOR “was the second-most frequently alluded-to database [n.b.- behind only Google] in student interviews.”

JSTOR is a wonderful resource for what it does best: making backruns of journals available back across the decades. Nowadays this seems like a normal thing to do, what with Google scanning everything it can, but when JSTOR started this was like manna from heaven for many researchers and students.

What JSTOR clearly is not, however, is a good starting point for students doing research. Why that is so should be obvious: for most JSTOR journals, the most recent years are not in the database. While JSTOR is slowly adding current content for specific journals through its Current Scholarship Program, only ~200 of the 1,400 JSTOR journals offer current content via the JSTOR interface.

Even today, as a full text storehouse, JSTOR is a goldmine, albeit one best accessed not by direct searching, but via a pointer from another resource that includes current content. Why, then, have librarians and faculty persisted in suggesting it to their students as a starting point? That’s a vexing question, but having argued with colleagues about this for years, I would ascribe it to, among other reasons, a traditional approach to research that assumes that students will consult multiple sources. We should know better.

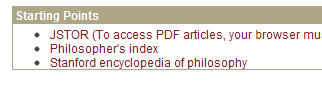

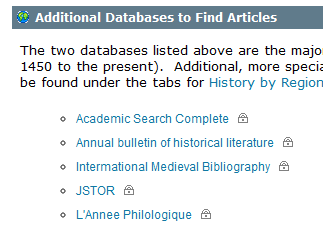

To drive the point home, here are some visual examples. The example at the top of this post comes from Kansas State University, which lists JSTOR as the most important database for political science, quite a feat of irony. In the field of philosophy, the University of Kansas lists JSTOR before The Philosopher’s Index while the University of Washington considers it among the six most critical for history.

while the University of Washington considers it among the six most critical for history.  Examples like this abound on library Web pages. Do we actually think students will notice that their JSTOR results lack research from the most recent five to seven years or so? Shouldn’t that matter? Moreover, the lack of current content is only one of JSTOR’s shortcomings as a place to do topical research. Its distinct amero- and anglocentrism as well as a somewhat elitist collection of journals (good business strategy but not academically sound) should be noted.

Examples like this abound on library Web pages. Do we actually think students will notice that their JSTOR results lack research from the most recent five to seven years or so? Shouldn’t that matter? Moreover, the lack of current content is only one of JSTOR’s shortcomings as a place to do topical research. Its distinct amero- and anglocentrism as well as a somewhat elitist collection of journals (good business strategy but not academically sound) should be noted.

One should really question whether JSTOR even belongs on the list of databases the library offers. It’s a critical part of our information offerings, but for the overwhelming majority of users, it should never be their starting point for research. Why then, does JSTOR feature so prominently on library Websites?

NOTIS, anyone?

On another expedition to our server/IT storage room today, I unearthed these gems. The red vinyl binders with “Teach ’em” on the spine just screamed legacy product, and when I pulled them out and saw that they were cassette tapes, I knew I had a good find. It only got better when on closer inspection they revealed themselves to be audio documentation for the NOTIS library management system circa 1993. Some of the better titles:

On another expedition to our server/IT storage room today, I unearthed these gems. The red vinyl binders with “Teach ’em” on the spine just screamed legacy product, and when I pulled them out and saw that they were cassette tapes, I knew I had a good find. It only got better when on closer inspection they revealed themselves to be audio documentation for the NOTIS library management system circa 1993. Some of the better titles:

- What’s Client/Server & What Does an Open System Really Mean

- Using a GUI for Expanding Patron Access

- What’s in the Future? MDAS and Infoshare

- Gopherspace: Exploration of the Information World Beyond NOTIS

and my personal favorite

- Cracking the Code: MDAS, OPAC, NOTIS: Where’s the Patron?

Seems we’re still asking that question.

There are 54 cassettes in all, which begs the question if anyone here (or anywhere) actually sat and listened to these. I suspect some did, but as with most such documentation, it was most likely dutifully shelved and forgotten. The binders and tapes on my desk are in pristine condition and show no signs of use. They are headed to the trash because I am not nostalgic about this stuff. Perhaps we should have a Museum of Dead Library Technology, but until there’s a place like that where I can send such items, they’re trash/recycling bound.

When I started in libraries, I worked with NOTIS on dumb terminals. It’s hard for me to grasp that we’ve gone from those (with documentation on cassette tapes!) to a wholly networked and virtual world in less than two decades. It’s old hat to marvel about the Web, but objects like this bring it all home.

Playing with the street urchin

What follows is a translation of an interview that appeared in the July 27th Leipziger Volkszeitung (article not online). Nina May interviewed Wolfgang Müller, the man behind the publisher VDM Dr. Müller, which I’ve criticized before (one/two).

Interestingly, Müller readily acknowledges that criticisms of his enterprise are largely valid, but notes that he doesn’t really care. What I find oddly refreshing is that he clearly has a dim view of librarians, and is not afraid to take digs at the profession. At least we know where we all stand. I suspect we agree on one critical point, too: if librarians find his products noxious, then it’s on us not to buy them, not on him to stop producing them. It’s a market, in his words.

Many thanks to Ms. May for granting permission to publish this translation:

“I couldn’t care less about content”

Press founder Wolfgang Müller explains why he sells printed Wikipedia articles with a clean conscience

He thinks editing is censorship and that the medium of the book is overrated. Wolfgang Müller, founder of the eponymous scientific publishing house, admits in this interview with Nina May that he contributes to the flattening of science. As long as he can make money, it doesn’t bother him. He publishes Wikipedia articles in book form, among other items.

Rechristening: Eintauchen is now Bibliobrary

For a while now, I’ve been mulling a name change for this blog. Eintauchen is simply too much of a riddle for those who don’t speak German. It would only follow that when it appears in search results that the name likely has a deterrent effect on potential readers.

For a while now, I’ve been mulling a name change for this blog. Eintauchen is simply too much of a riddle for those who don’t speak German. It would only follow that when it appears in search results that the name likely has a deterrent effect on potential readers.

Not wanting to completely lose the German origin of the blog, however, I tried to think of a good name to replace it. It had to meet the following criteria:

- expressible in a domain, i.e.- name and domain are the same

- be at least somewhat easily speakable in both German and English

I first came up with bibrarian.net, but realized that if intonated with a long initial i it would sound as if I were publicly expressing (incorrect) personal preferences. Moreover, it would fall too close to librarian.net, and that’s just not cool to do to Jessamyn and would make me look like a squatter, to boot.

My brain, my career, and my professional circle span both the North American and German spheres, so I just had to reflect that in the name, which is how I hit upon Bibliobrary (Bibliothek + library = Bibliobrary). Amazingly, the domain was even available.

Many thanks for reading, and I hope the new name is less intimidating.

How not to do customer service

Does this sound familiar to anyone? You want to give your money to some company for a good or service, but they are too incompetent / disinterested / confused to take it from you. This seems to happen more and more frequently as online commerce “matures.” Case in point:

MPOW provided me a lovely little HP Mini 5103 netbook. It’s tiny, runs for nearly ten hours on a charge, and now that I’ve removed Windows and made it a quick-bootin’ open-source-lovin’ Ubuntu machine, it makes me happier than any computer I’ve ever used. There’s just this one thing …

That battery with the super long life is kind of fat, well 22 mm thick to be exact. That’s not large, but what it means is that the battery extends beyond the chassis of the computer. The upside to this is that it tilts the keyboard at a nice angle. The downside is that it makes the netbook somewhat harder to fit into a small bag, and it adds weight to an otherwise featherweight machine.

Googling around convinced me that there might be a smaller profile battery available for this netbook, but the various third-party vendors are vague as to which models which batteries fit, and they also tend not to give dimensions for batteries. Naively, I thought I’d just ask HP. Ha.

In praise of friction

Friction, not fiction. You read that right. Nothing against fiction, of which my readerly side is rather fond, but this post is about friction and the good it can do.

At this point in my career, I have come to accept that I am a somewhat dyspeptic and abrasive librarian, as opposed to a cheerleading, librarian-affirming librarian. Why? Well, if I had to offer answers, I would say that it stems from a belief that we need more tension in our field of the type that leads to open debate and the challenging of assumptions, no matter how dearly held. What librarians generally consider conflict most faculty (or most people in any profession) would consider to be a polite disagreement. Rarely are speakers challenged directly, and, if so, only after the interlocutor has effusively praised the speaker.

We also need to be more cantankerous (to borrow a former colleague’s word) toward our vendors, since playing nice and entering into ‘partnerships’ has given us a crapload of mediocre yet overpriced software and services with which we constantly struggle. Let’s raise a little ruckus, poke some sensitive spots, and get things moving. And above all, we need to learn to vote with our money. We don’t like your product? None for you!

For my own part, it comes to this: were I just spouting off to experience catharsis, I’d feel bad, but there’s always an agenda, and there are ideas, so it’s not like I’m just tearing down without offering ideas for building up. Friction can be a good thing when applied judiciously.

Blast from the past

While wandering around this afternoon in our server room/IT storage cave, I ran across this pristine copy of the OCLC Terminal Software User Guide ca. 1988, complete with laminated keyboard shortcut guide and function key decoder.

For me, the 5.25″ mint condition floppies are the pièce de résistance of the whole lot.

And now I will do my part to clean up our cave and put the whole mess in the recycling/trash. Why are libraries/librarians so bad at throwing out useless junk?

The retirement wave myth

Recently, reading the comments on a library blog post, I read a lament from a newly minted librarian about the lack of jobs and how the situation would be remedied would only the old librarians retire. The comment was not meant to be ironic, I fear.

Regardless of their chosen academic career track, who hasn’t heard at some point that a wave of retirements is going to sweep away the top of the profession, opening up many plum jobs for the Young Turks? I heard it in the early 90s when starting a PhD in German; not sure how much more wrong one could have been. I heard it when I went to library school, too, and I have yet to see any such wave.

Most retirements do not lead to a one-to-one replacement, and it’s been more or less accepted for years that the staffing in academic libraries is contracting over time. 1 The fact of the matter is that any open position in any organization gets tossed into the personnel budget hopper, and what comes out may or may not resemble what went in, both in level and responsibilities. In libraries, the personnel budget has been under assault for years given our need to maintain collecting levels, so downsizing is more or less built in.

I think it’s time to quash this particular myth once and for all. What makes any new graduate of any stripe employable in academia is a profile that an institution needs at that moment. Given how rapidly fads come and go in academia, trying to project what universities will need ten years in the future is about as likely to succeed as your lotto numbers for the week. Better is to have a broad skillset that is constantly under revision, where useless skills are let go and new are acquired.